Before the bombing, the city had enterprising plans to draw attention to its downtown. Now those plans matter more than ever.

by Mark Alden Branch

For Oklahoma City’s boosters and business leaders, the April bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was a grotesque parody of their wildest dreams. For years, residents of this 106 year-old city had struggled to develop an image for their low profile community. Then, just when an ambitious downtown improvement program was about to get under way, the world’s attention was seized by the grisly devastation of the Federal Building.

For Oklahoma City’s boosters and business leaders, the April bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was a grotesque parody of their wildest dreams. For years, residents of this 106 year-old city had struggled to develop an image for their low profile community. Then, just when an ambitious downtown improvement program was about to get under way, the world’s attention was seized by the grisly devastation of the Federal Building.

Nonetheless, the series of projects initially aimed at drawing attention and tourists to downtown Oklahoma City is going forward, and has gained new importance in a metropolis trying to move past its recent tragedy.

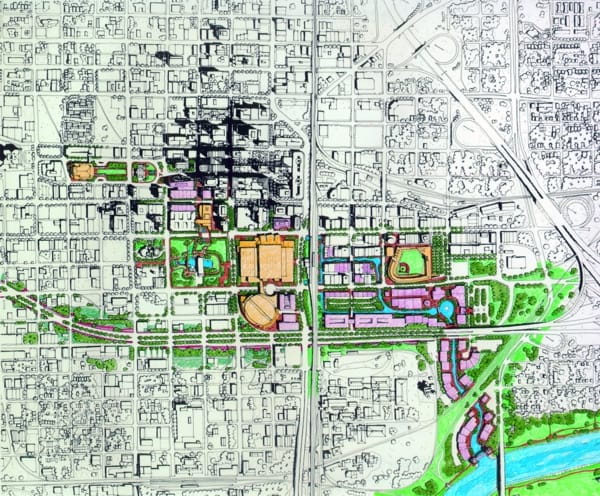

Oklahoma City’s plan, known as MAPS (for Metropolitan Area Projects), will use the proceeds of a temporary one-cent sales tax increase to build $285-million worth of public facilities, mostly downtown.

Where previous urban renewal plans in this city of just under $1 million have collapsed under their own weight, this one will succeed, civic leaders say, because the money to implement is assured.

The bombing and its widespread damage to buildings on the north side of downtown will have little effect on the plan, which is concerned mainly with downtown’s south edge. However, city officials are considering new planning efforts for the area hardest hit by the explosion. This summer, the National Endowment for the Arts is paying for a charrette that will bring in planners, architects, and artists to consider the future of the bombing site and the area immediately surrounding it.

The General Services Administration, which owned the Murrah Building, will have the final say over what is done on its site, but public sentiment runs strongly toward building a memorial there in lieu of a new building. The GSA may decide not to rebuild at all, but instead relocate federal offices into existing downtown office buildings.

The General Services Administration, which owned the Murrah Building, will have the final say over what is done on its site, but public sentiment runs strongly toward building a memorial there in lieu of a new building. The GSA may decide not to rebuild at all, but instead relocate federal offices into existing downtown office buildings.

In Pei’s Empty Footsteps

The MAPS plan was conceived so as to avoid the fates of earlier forays in urban renewal, which nearly killed the downtown. The city implemented the demolition phase of a 1964 master plan by I.M. Pei, but didn’t follow through with much new construction; facilities such as a downtown mall were planned but never built. The demolition left gaping holes in the central business district and, just east of downtown it wiped out an entire African-American neighborhood.

The city did manage to build a trio of new attractions on the downtown’s south edge: John Johansen’s celebrated Mummers Theater of 1970 (recently renovated and renamed the Stage Center), the Crystal Bridge botanical garden by Conklin Rossant (P/A, March 1989, p. 92), and the Myriad Convention Center. But the disappearance of retailing, the development of an air-conditioned tunnel system, and the proliferation of vacant lots have conspired to turn a formerly diverse downtown into a dispiriting office zone. Foregoing the heroic task of comprehensively remaking the downtown, the current strategy concentrates on a series of individual projects it is hoped will spur spin-off investments around them.

“The projects are kind of like anchor stores in a mall,” says Jim Bruza of master plan architects Frankfurt Short Bruza. “The areas between them will become good sites for private development.”

The largest chunk of new sales tax money will go for an $80-million sports arena intended to attract a National Hockey League franchise. (The city’s Blazers have the best attendance record in the minor leagues.) The minor-league baseball team, the 89ers, will get a new $23-million ballpark in the Bricktown warehouse district east of downtown. The WPA-era Civic Center Music Hall will be renovated at a cost of $37-million, a new $15-million central librar y will be built, and the Myriad Convention Center will receive a $30-million renovation and addition by the local firm Glover Smith Bode with Thompson Ventulett Stainback & Associates of Atlanta.

A Canal to the Canadian River

An especially tough problem was how to lure conventioneers across the elevated railroad tracks that separate the convention area from Brictown, where brick warehouses have been transformed in recent years into an entertainment district. The solution, inspired by San Antonio’s Riverwalk: create a below-grade canal. The canal will originate in front of the convention center, pass through a portal under the tracks, and trace the route of a Bricktown street to the ballpark which is to be designed by ADG of Oklahoma City with David M. Schwartz / Architectural Ser vices of Fort Worth. At the ballpark – which, attentive to the example of the Baltimores’ Camden Yards stadium, incorporates an existing warehouse into it’s design – the $15-million waterway will make a 90-degree turn and meander toward the Canadian River.

The canal, with walkways, trees, and outdoor cafes along its edges, will lie 14 feet below grade, presenting opportunities for converting Bricktown basements into an additional level of retail or entertainment space. If the corridor develops as envisioned by Frankfurt Short Bruza, it will spawn a lively succession of activities alongside the canal and above it at the main level of the renovated warehouses. Sheltered by the street walls of the warehouses, the canal could be an oasis in a downtown that is often hot, dry, and windy. The canal will be convincing, however, only if its accompanying stairs, ramps, and terraces respect the dignity of the plain, muscular warehouses.

Planners harbor no illusions about the level of urbanity that Oklahoma City can achieve; the master plan document drily acknowledge that “a plan for a dense pedestrian city like Rome of Florence would be a mistake.” Substantial retailing and housing are all but gone from downtown, and city officials don’t expect them to come back except in the form of specialty stores and residential loft conversions in Bricktown.

Like many Western cities, Oklahoma City came of age with the automobile. Its 20th-Century patterns of development – which have resulted in a population density lower than that of any other U.S. city – make it unlikely that a traditional dense urban character can ever be created within its 604 square miles. Instead, learning from theme parks, atmospheric ballparks, festival marketplaces, and other tourist lures, the new plan arranges attractions to create a pedestrian environment of a different kind – one based on special events rather than on daily routines. Whatever Oklahoma City’s downtown may not be, it will be a destination – for conventioneers, for tourists, and, more than in recent years, for its own far-flung populace.